The Muleteer in the Lebanese Novel: Social Transformation in the Era of Global Capital

Joan Chaker

| Research on the Arts Program | 2018 | Lebanon

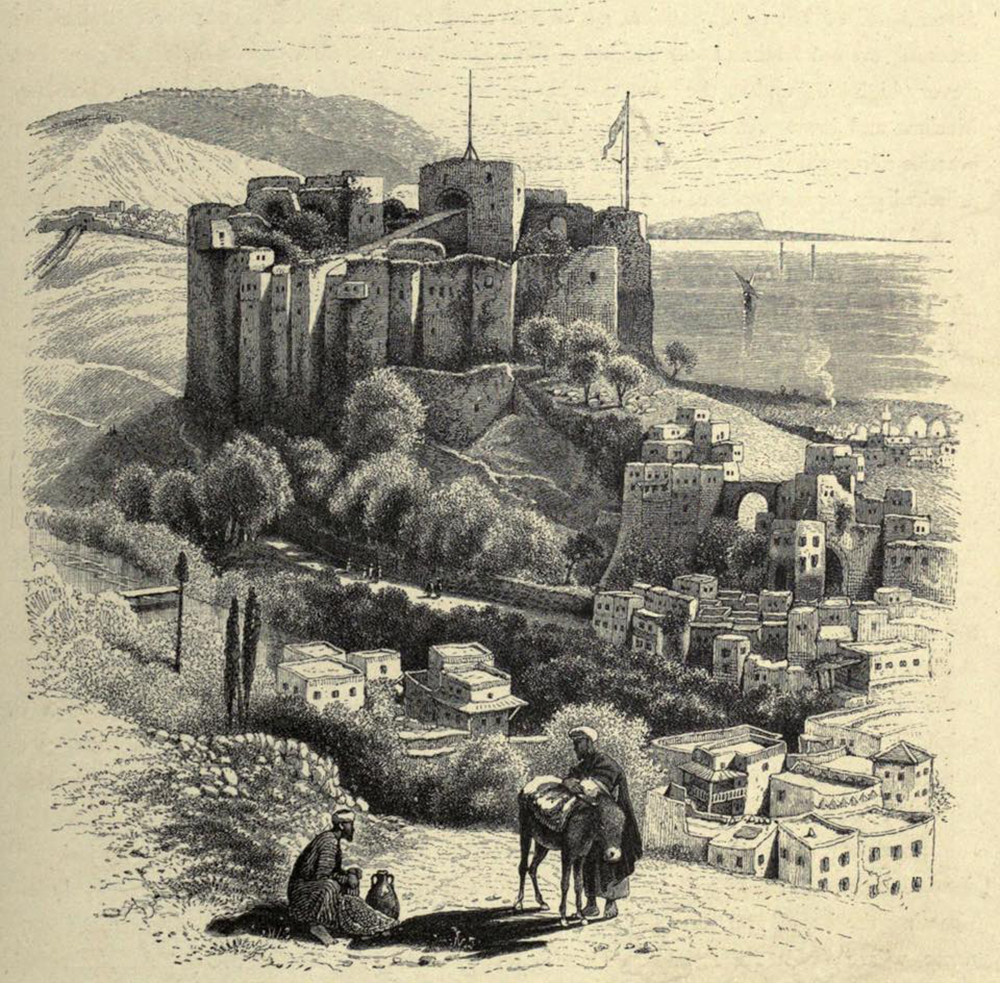

This study revolves around Lebanese novels that feature, among their principal characters, a mule driver – that obscure peasant who, rather than work the land, makes his livelihood in the transport of goods and persons on mule-back.

After tracing the imprint left by the Lebanese muleteer in collective consciousness as a Robin Hood-like social bandit defending the peasantry against state taxation and capitalist extraction, this research questions the significance of that character’s repeated appearances in the burgeoning literary genre of the novel. The novel in itself was the result of a tension between the traditional and the modern. In the global South, it was also the product of the encounter with the West. Where the new literary form reflected a desire to modernize, resort to heritage could be understood as a defense against dissolution in a globalizing world – both on the part of the author and his readers, all members of an evolving middle class. In the eloquent words of Walter Benjamin: “The birthplace of the novel is the solitary individual.” Which is why the literary genre recurrently assigns pride of place to the muleteer who, attuned to the basic rhythms of rural life, experienced firsthand the dissolution of community. Drawing parallels between Lebanon and contemporaneous contexts across the rural global South, this study makes a case for the novel centered on the customary rural transport worker as a coherent sub-genre that cuts across cultural contexts to express the visceral angst that pervades rural communities on their transition into liberal capitalism.